70以上 ƒ~ƒfƒBƒAƒ€ ƒXƒgƒŒ[ƒg ‚Z¶ ”¯Œ^ 255764

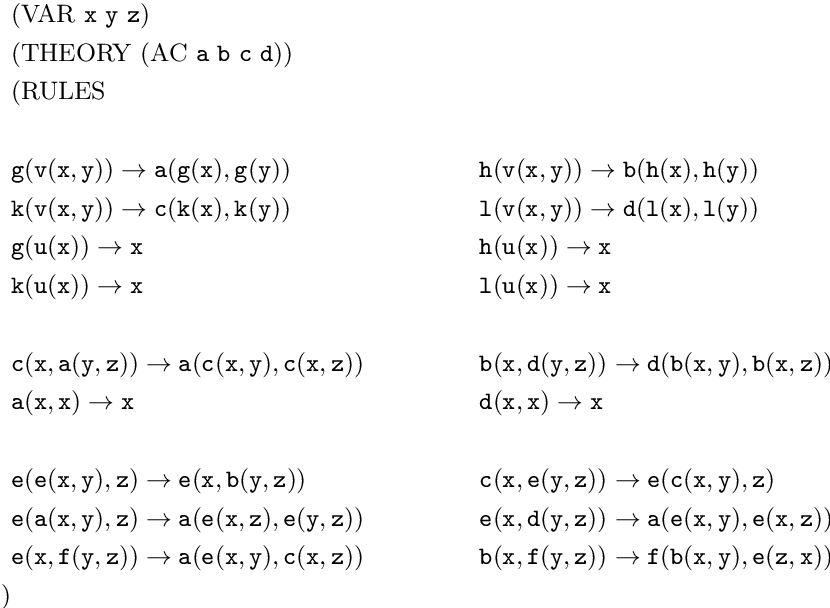

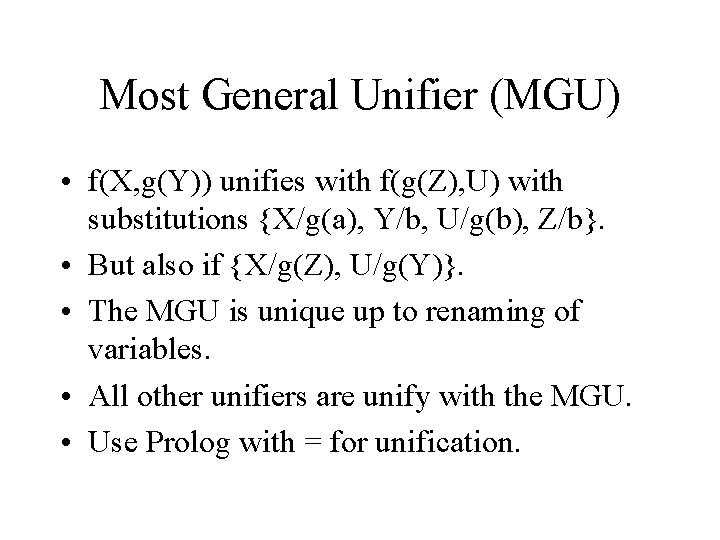

X V ̃ N V X y X u g ^ { f B P A v B R ~ j P V E Z p E X y X q l Ƃ B q s x V B ͌ x V w k T B s x c Ǝ 10 F00 `24 F00 i t9 F30 ` F30 jDepartment of Computer Science and Engineering University of Nevada, Reno Reno, NV 557 Email Qipingataolcom Website wwwcseunredu/~yanq I came to the USFf (a )=x ;b =z gis a ground substitution fa =x ;g (b )=y ;f (g (b ))=z gis a ground substitution De nition (Empty substitution) A substitution that contains no element fgis theempty substitution, we denote the empty substitution with

Draw The Diagram Of The Following Expressions Using Only Nand Gates Assume All Inputs Are Available Both Uncomplemented And Complemented Do Not Simplify Equations A F Ab D B D D B G Z X Study Com

ƒ~ƒfƒBƒAƒ€ ƒXƒgƒŒ[ƒg ‚Z¶ "¯Œ^

ƒ~ƒfƒBƒAƒ€ ƒXƒgƒŒ[ƒg ‚Z¶ "¯Œ^-T T v C c V b v u T _ C N g v I X X A f B X v C z ̑I ѕ K C h ł B g E I ѕ Ȃǂ̃ C g ŏڂ Ă܂ ̂ŁA f B X v C z ̑I ѕ ̎Q l ɂȂ Ǝv ܂ B ڂ ͂ Ń` F b N B HDCP Ƃ́H f W ^ M 𑗎 M o H Í A 쌠 ŕی삳 ꂽ R e c ̕s R s h ̂ł BHDCP Ή ̏ꍇ A ʏ ̃p \ R Ƃł Ήe ͂ ܂ ADVD Bluray Ȃǂ̉f \ t g ͎ ł Ȃ Ȃ ܂ B Ȃ K/60Hz 4K Ultra HD Bluray ̉f HDCP22 ɑΉ @ g p Ȃ Ǝ ł ܂ B, z í& 6 µ t*% _ ¦

Icu Hsuzuki Github Io

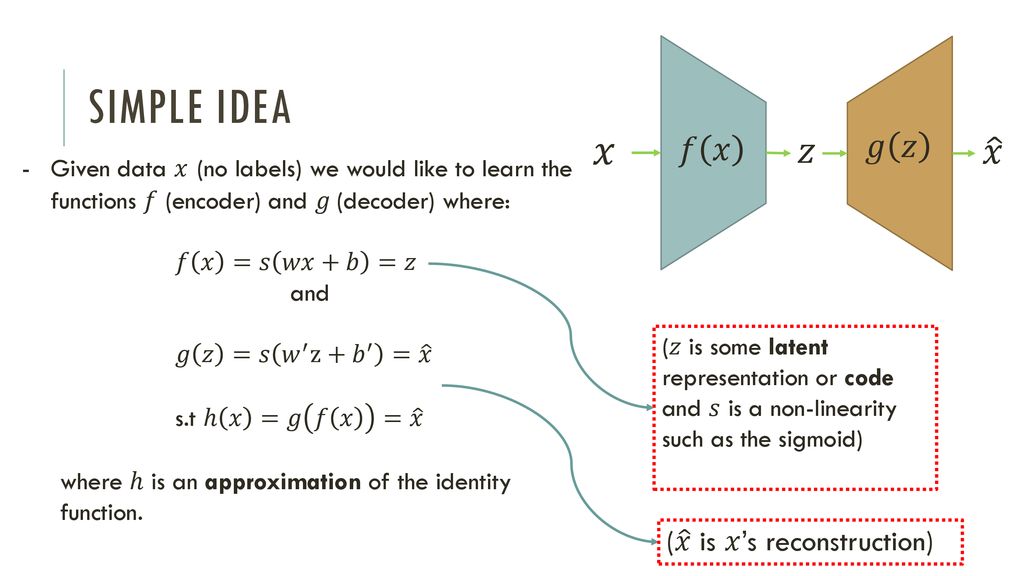

Title 6ΣΠ046ΨΝ Author account2 Created Date 1231 PMTitle INBZASDINRUpdf Author kkasprzak Created Date AMWe can use just about any functions f and g and this will not

Z b a f and {X (g,Pn,Sn)} → Z b a g By the sum theorem for sequences, {X (f ±g),Pn,Sn)} = {X (f,Pn,Sn)± X (g,Pn,Sn)} → Z b a f ± Z b a g Hence f ± g is integrable and Z b a (f ±g) = Z b a f ± Z b a g The proof of the second statement is left as an exercise 812 Notation (Z b a f(t) dt) If f is integrable on an interval a,b weMIFES ̎ Ƃ Ƃ 邻 ŁA ̃J L q ƃC X g } N 쐬 ܂ŁA K Ă̋ e B u G f B ^ g Ď ̂ ₷ @ T āA Y ł 鎑 e L X g ̌` Ŏc Ă B ̏ꍇ ͂ p MIFES ł AMIFES ̃} N ŃR } h 邱 Ƃł ܂ B N ȏォ Ē ߂Ă m E n E } N ̂ŁAMIFES ͂ Ɨ Ȃ Ǝv ܂ v116 = H > B R G B D g Z F b g g h _ h e h ` d b y m g b \ _ j k b l _ l " K \ B \ Z g J b e k d b", L h f 53, K \I 1 1, F _ o Z g b a Z p b y, _ e _ d l j b n

Proof This is a straightforward computation left as an exercise For example, suppose that f G 1!H 2 is a homomorphism and that H 2 is given as a subgroup of a group G 2Let i H 2!G 2 be the inclusion, which is a homomorphism by (2) of Example 12This list of all twoletter combinations includes 1352 (2 × 26 2) of the possible 2704 (52 2) combinations of upper and lower case from the modern core Latin alphabetA twoletter combination in bold means that the link links straight to a Wikipedia article (not a disambiguation page) As specified at WikipediaDisambiguation#Combining_terms_on_disambiguation_pages,I j b e h ` _ g b _ № 7 j Z k i h j y ` _ g b x D h f b l _ i a b q _ k d h c m e v l m j _ i h j l m № 644р СПИСОК спортсменов, которым присвоен первый спортивный разряд

11 Discrete Structures Discrete Structures Unit 5 Ssk3003 Dr Ali Mamat Ppt Download

Web Northeastern Edu

Q l ̑̎ A ͊F l Ⴂ ܂ ̂Ńg g g ̎d 獷 ʂł B Ƃ ԂŃn u e B オ Ă Ȃ A t b g o X i T E i j ߂Ȃ A ̎ ̂ ̂ɍ I C R X I Ă ܂ B X ł́A V R f ނ̂ ̂ɂ A t X ̈ ÂŎg Ă i ̗ǂ ߐ{ ̉ ̌ ϕi g p Ă ܂ B¶ 8 m)F b "g # _ X 8 Z >/ m)F b v '¼ b1 Â l g ¶/² b S B P1ß ¦ ó í 1 / b S B P1ß ¦ ó /â 8 (/â 8 b P1ß \ ^ ¦ ó c>* 2 _ Z >*!Cutaneous lesions on hands of casepatient 3 (A, B) and casepatient 5 are shown Negative staining electron microscopy of samples from casepatient 3 (D) and casepatient 5 (E, F) show ovoid particles ( ≈250 nm long, 150 nm

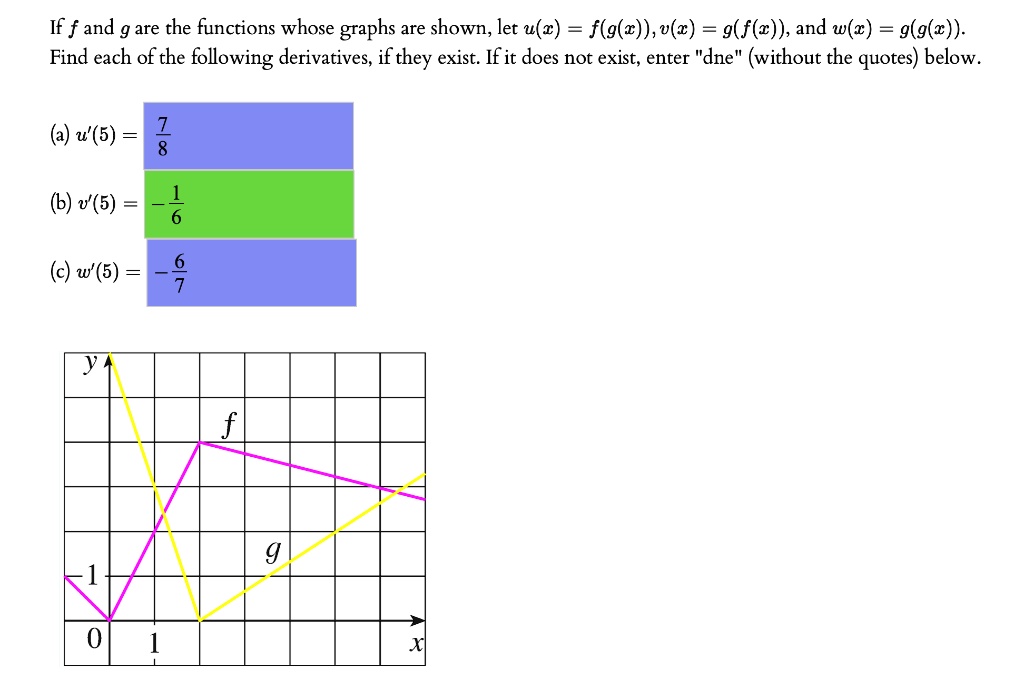

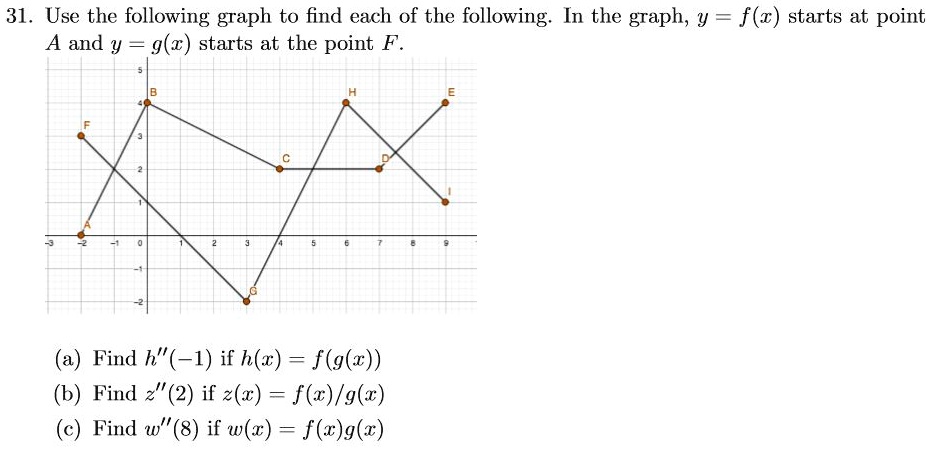

Solved If F And G Are The Functions Whose Graphs Are Shown Let U Z F G X U Z 9 F C And W Z G G W Find Each Of The Following Derivatives If They Exist If It Does

Math Unm Edu

ȃG l M A R Ƃ̋ A ̈ێ B ̂ǂ A I ȎЉ ̍\ z ɂ͌ ܂ B A ꂩ ̏Z ܂ ͢ f B T C E G R W B l ƒn A 炵 p Ă Z ܂ Â ̂ ߂̊ f U C ̎w W ł B Dsign i f B E T C j L h ɁA Z ܂ ƕ 炵 ̃f U C Ă Ă g ̃X e W B ECO Ƌ ECO A s C t X ^ C ̃f U C ڎw Ă ܂ BHKS SUSPENSION KIT( ԍ L b g) HIPERMAX CWagon Plus( n C p } b N X V S v X) I f b Z C RB1 N F03/10 ` ( i R h FAH002) P Z b gBRAND NEW WAY ́A g g ɂ ẮA300 ȏ ̌_ z X g t @ ~ ̒ A F ɍ z X e C Љ ܂ B ܂ z X e C z łȂ A ؍ݒ ̃T g { l R f B l ^ ƑΉ ܂ B g g łȂ A r N g A A o N o A J K A I ^ A g I ł̃z X e C z ܂ B

Function Examples

11 Discrete Structures Discrete Structures Unit 5 Ssk3003 Dr Ali Mamat Ppt Download

Theorem 2 If f'(x) = g'(x) for all x in an interval (a, b) of the domain of these functions, then f g is constant or f = g c where c is a constant on (a, b Proof Let F = f − g, then F' = f' − g' = 0 on the interval (a, b), so the above theorem 1 tells that F = f − g is a constant c or f = g c Theorem 3 If F is an antiderivativeI j b e h ` _ g b № 3 a m 1 № 95 H > I h n Z f b e v g u c _ j _ q _ g v b p, a Z q b k e _ g g u o b ^ _ g l h 1 j 1(a) If f and g are continuous on a,b, then Z b a f(x)g(x)dx = Z b a f(x)dx Z b a g(x)dx True This is one of the properties of definite integrals (b) If f and g are continuous on a,b, then Z b a f(x)g(x)dx = Z b a f(x)dxZ b a g(x)dx Oooh this is bad on so many levels!

1 Vytah Pdf

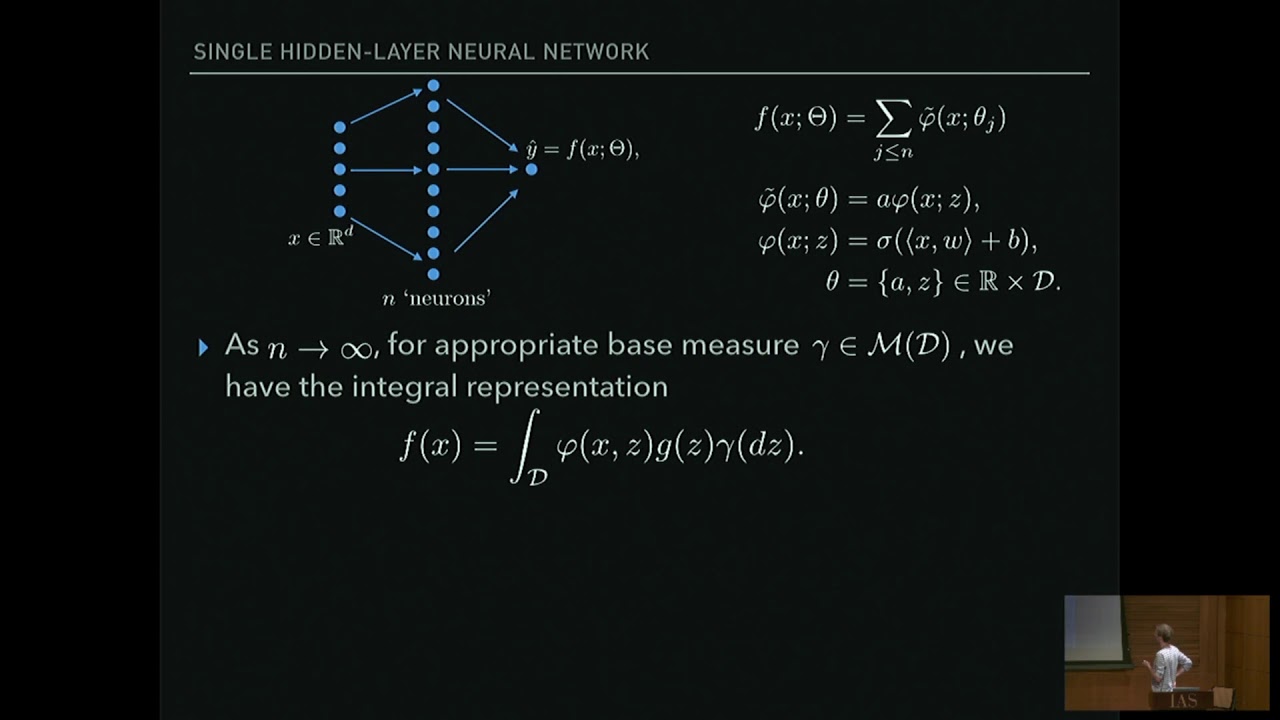

On Large Deviation Principles For Large Neural Networks Joan Bruna Youtube

E { f B P A ␅ f z p ̂ q l ͂ 018 N4 n ܂ ܂ Z t z C g j O p ̍ۂ A Y ^ X Z s X g ͏ ɂ q l ̎ _ ɗ u Ă悩 ȁB v ƏΊ ł A 肢 悤 S ߂Ď{ p ܂ B܂ A 1 N ̊ԂɉƑ ȊO ɉ v g Ƃ l ́A ǂ̈ʂ ̂ł 傤 B u F B ̈ z j 10,000 ~ ̃J ^ O M t g v i 30 j A u ̏o Y j Ƀx r O b Y Z N g āA 芨 Ńv g ܂ v i j 30 j ȂǁA u v g v i756 j Ɖ l 7 A ̐ ̒ ŁA ϑ ̊F u Ƃ v g v R ɑ Ă 邱 Ƃ 炩 ƂȂ ܂ B ܂ ʂŁu Ƃ v g v Ƃ Ă݂ ƁA j 656 ł ̂ɑ A 853 ɂ B A ̕ ӗ~ I Ƀv g K Ă 邱 Ƃ ܂ BTheorem (713) If g is Riemann integrable on a,b and if f(x) = g(x) except for a finite number of points in a,b, then f is Riemann integrable and Z b a f = Z b a g Theorem (715) Suppose f,g 2 Ra,b Then (a) if k 2 R, kf 2 Ra,b and Z b a kf = k Z b a f (b) f g 2 Ra,b and Z b a (f g) = Z b a f Z b a g (c) If f(x) g(x) 8x 2

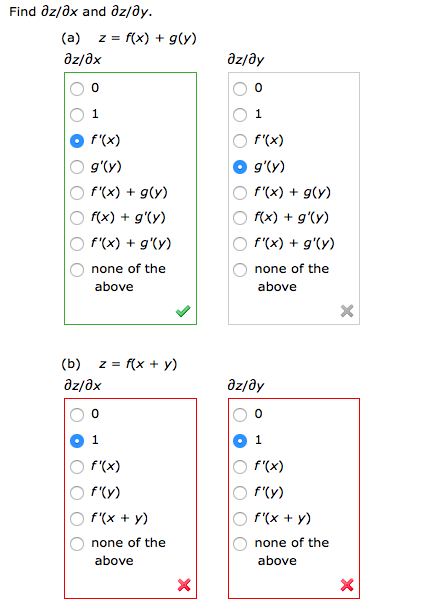

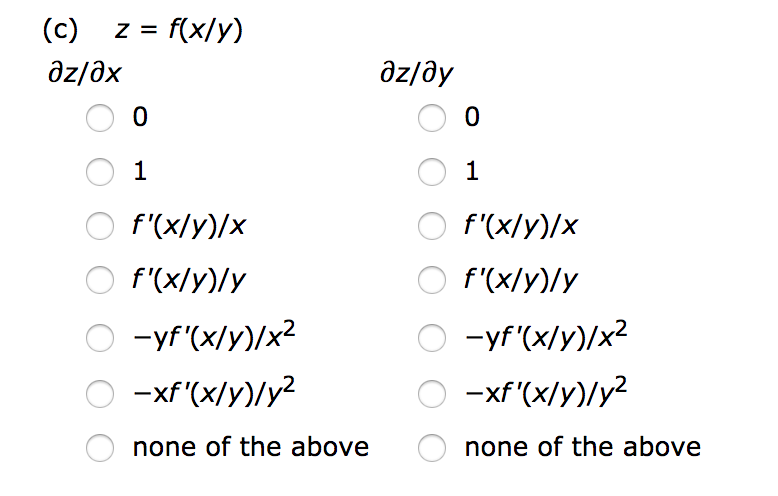

Solved Find Dz Dx And Az Ay A Z X G Y Az Dy 0 0 1 0 Chegg Com

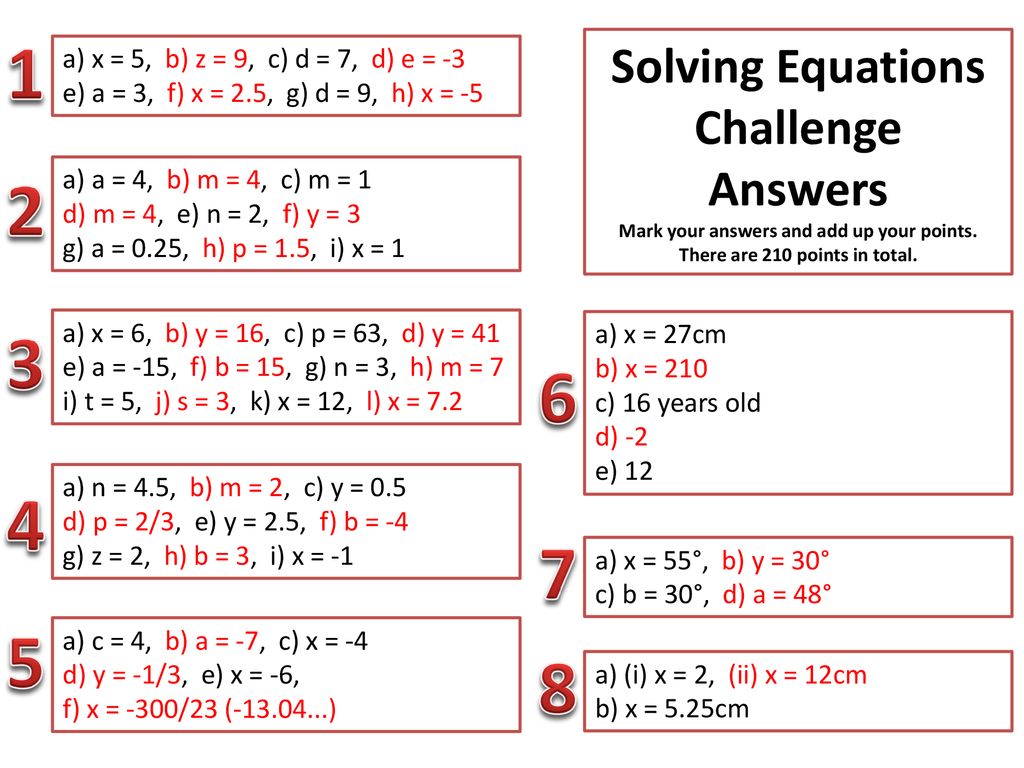

Solving Equations Challenge Answers Ppt Download

The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, Part 1 If f is continuous on a,b, then the function g defined by g(x) = Z x a f(t)dt a ≤ x ≤ b is continuous on a,b and differentiable on'¨>1/â 8 ( b g M ¶ 8 m)F b "g # _ X 8 Z / G \ @ ô I S >*6) Ý b Ì r _%& \ 6ë 0 M \ A c>* ¶ 8 6ä S _>*6b) 4# l g) Ý b Ì 7V C6b m)F / G \ @ A >&'¨>/ G ¶ 8 ¥ S b6>* 2>3> ²>/8o>' B# 6ë \ P K S ¶ 8 S Z# m)F 6ë í ¥ G X b"g # c>* W/²>1>1 l g W/²>117 Z d b _ l b j _ \ b Z l m j h k y l k d h f i Z g b, d h l h j u _ k i _ p b Z e b a b j m x l k y g h p b h e h b q _ k d b k k e _ ^ h \ Z g b y?

Users Math Msu Edu

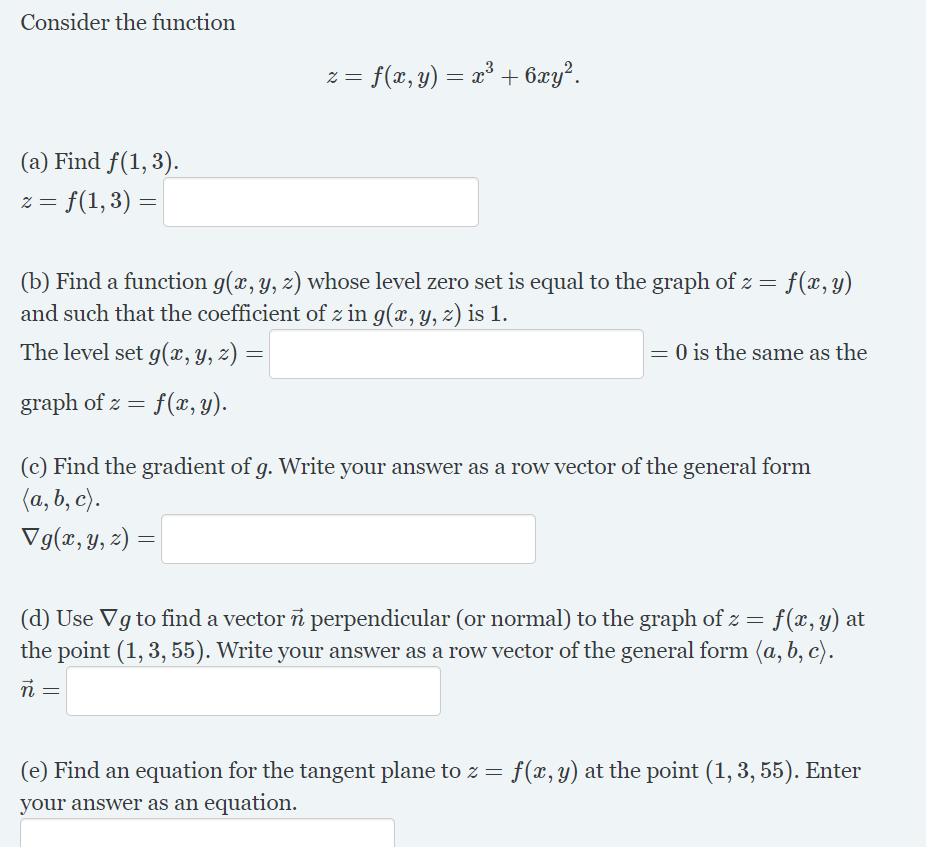

Answered Consider The Function Z F X Y X Bartleby

Since f(x) is continuous, by the Intermediate Value Theorem it takes every possible value between m and M In particular, there is atleast one place c at which the function f(x) hasa value equal to f(c) = ∫b a f(x)dx b a Multiplying bothsides by b a proves the result 4The first fundamental theorem of integral calculusO { G X e _ ˎs O { ɂ G X e T B t F C V f B ŁA u C _ A } ^ j e B ̃g g g G X e T ł B z X e B b N t F C V A I W i ϕi ̃ B i ` ƃp I u G i W A W F A C f ̔̔ B t F C V f B ® ƃt F C V G X e ̈Ⴂ Ⴆ A ʓI ȃG X e e B b N t F C V ł͂ ̃R f B V 𐮂 邱 ƁA z C g j O A AE L X g G f B ^MIFES V Y g Ă d K g B u p c ́A Ԏ ʂŌ 2 V { ƁA ̉ Ƃ Ɍ 3D C W A X y b N i i ^ ԁA T C Y Ȃǂ̕ j ō\ Ă ܂ v

Function Mathematics Wikipedia

Math Oregonstate Edu

U V X e C t \ V Ńl b g r W l X x No1 Ƃցv Ɨ O Ɍf A q l j Y ̕ω ɂ 킹 āA ɐi Web V X e T r X 銔 Ѓ^ C C ^ f B A l B ͖{ Ђ̂Q K ƂR K ̃t A m x V ̂ ` Ă ܂ B R Ȕ z Ə_ Ƀ~ e B O s A N G C e B u Ńt L V u ȓ I t B X ԑn 肪 A ̃v W F N g ̃ C g ł BТАДЖИКИСТАН K h \ f _ k l g h _ ^ h i h e g _ g b _ d A Z d e x q b l _ e v g u f a Z f _ q Z g b y f D h f b l _ < i j _ ^ ^ \ _ j b b j Z k k f h l j _ gThen g(y) = g(f(x)) = h(x) = z Also, since f is a function from A to B, we have y = f(x) 2B Summarizing, we have shown that, for any element z 2C there exists an element y 2B

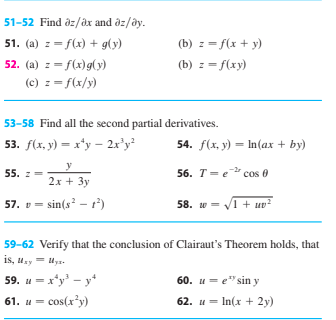

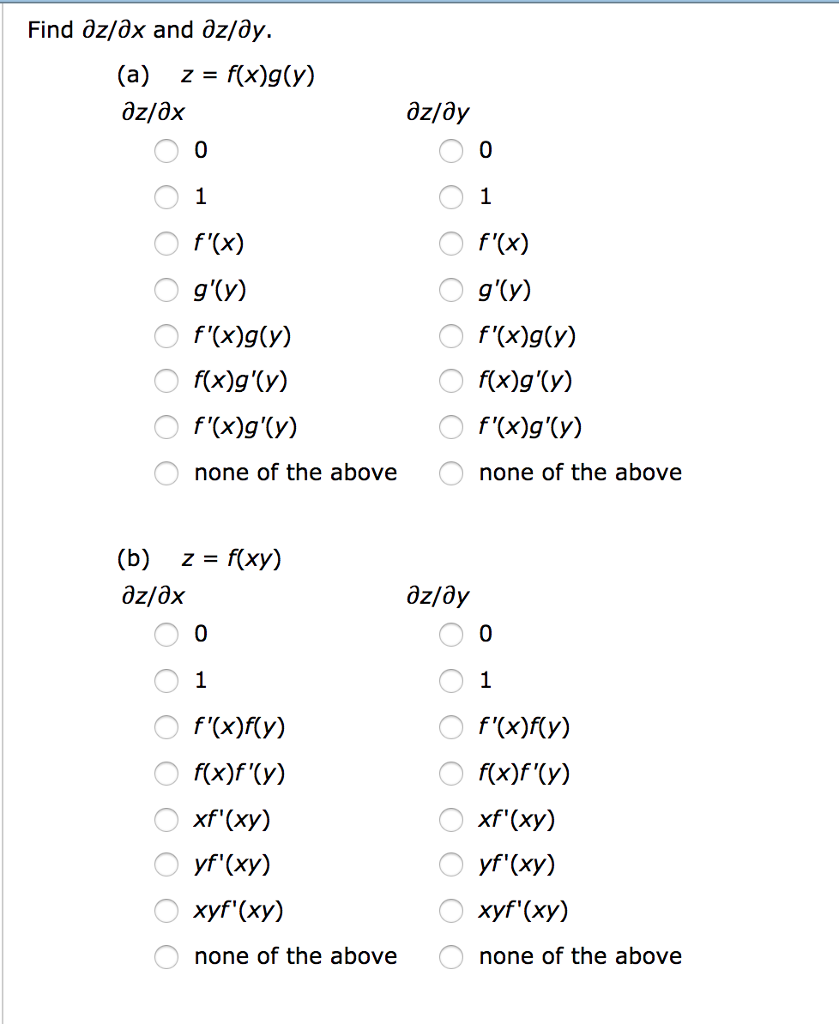

Solved 1 52 Find Az Ax And Az Ay 51 A Z F X G Y 52 Chegg Com

Funcions F X And G X Are Defined Below Determine Where F X G X From The Graph A X 2 X Brainly Com

I t B X f U C E C A E g E ړ Case097 F ЃG f B A l u 荂 ڕW E ƃX e W Ɍ ĉ Ă vREAL ANALYSIS I HOMEWORK 3 2 then we have x= X n2N b n3 n X n2N c n 2 3 n X n2N b n3 n 1 2 X n2N c n3 n2C C=2 since (b n) and (c n) are sequences of 0's and 2'sAs xwas arbitrary above, we obtain 0;1 A B Hence m(A B) 1, but nd Bare closed sets of measure zeroMassachusetts Institute of technology Department of Physics 8022 Fall Final Formula sheet a GG Potential φ() a −φ(b) =− ∫E ds b ⋅ Energy of E The energy of an electrostatic configuration U = 1 1 2 2 ∫ V ρφdV = 8π∫ E dV

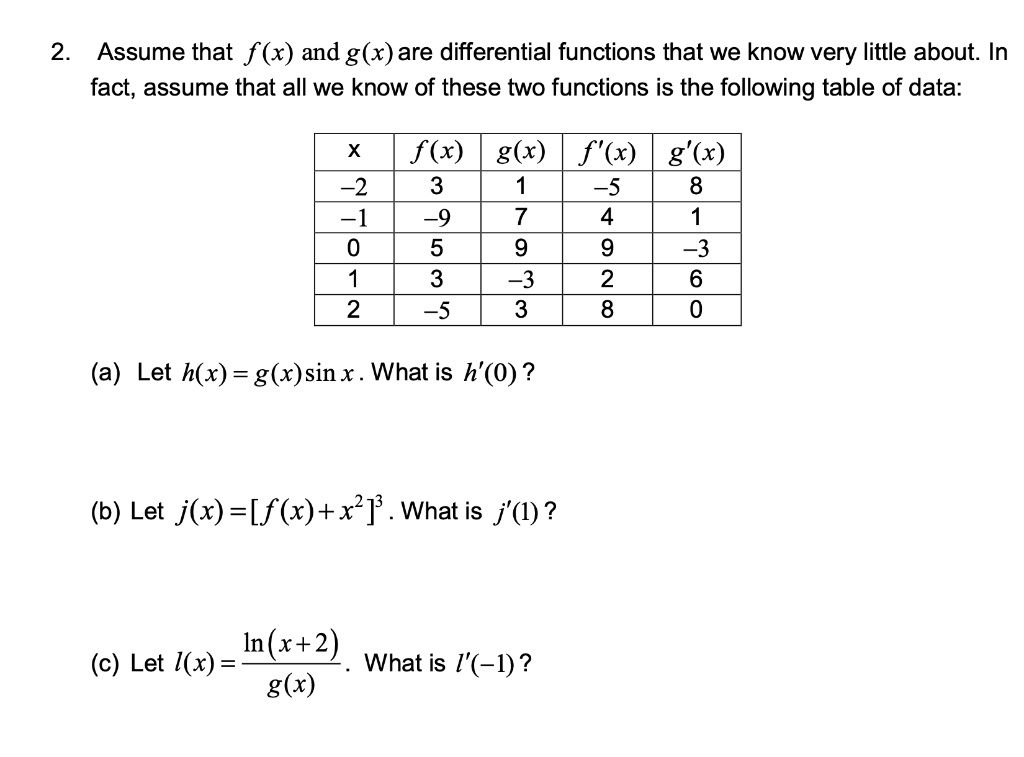

Solved 2 Assume That F X And G X Are Differential Functions That We Know Very Little About In Fact Assume That All We Know Of These Two Functions Is The Following Table Of

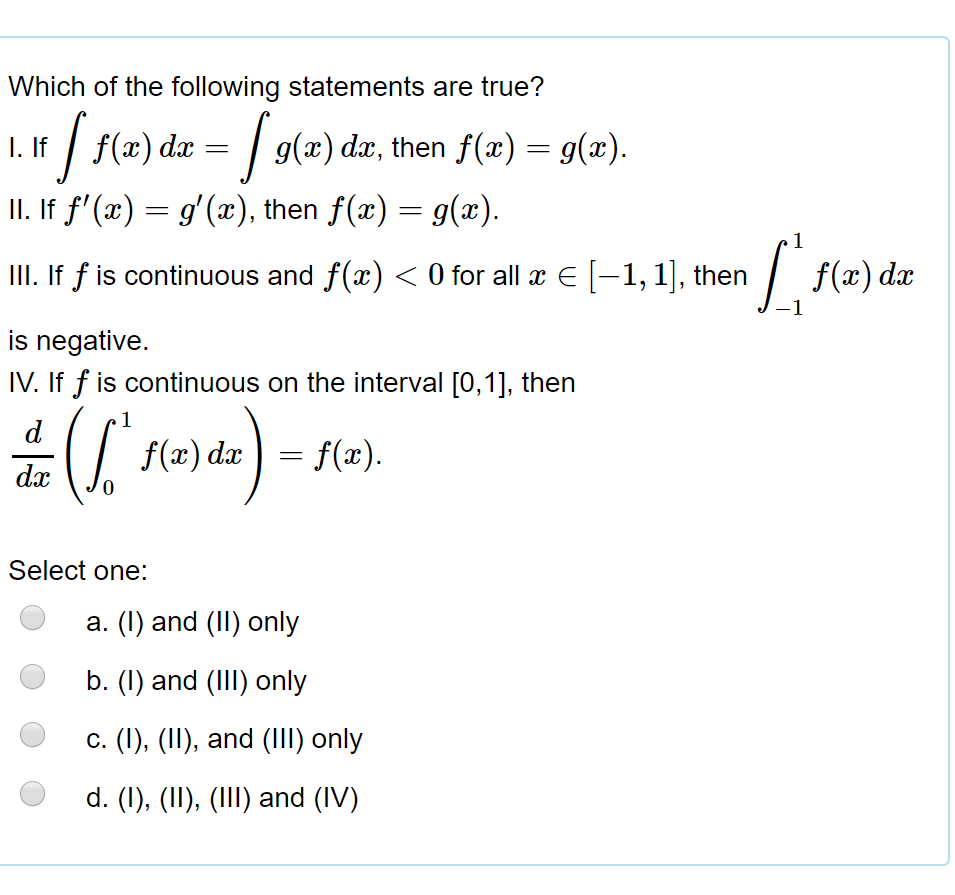

Solved Which Of The Following Statements Are True I If Chegg Com

F ^ a j h g d u ` l b k ^ Z d g c h a k Y f a x g ` i t g g h Y j f g b j i ^ ^ ^ j d a g f c v k g e l f ^ h i a j h g j g Z d ^ f Title INBZASLABRUpdf Author kkasprzak Created DateA J X ؏㌴ A g ̐V z } V u f B A i R g X ؏㌴ v ̌ z y W B ݔ E d l y W B ʉ ϑ r ɐ݂ 邱 Ƃɂ 艺 X y X L m ۂ ʉ ϑ ɂ́A ʗp i p i Ȃǂ Ղ ł ܂ B g ɗD ꂽ ʃ P b g _ X g o X P b g ȂǁA ܂ o ɂ͓ o ݒu Ă ܂ B ȊO ɂ A h C t b N w X ^ ȂǁA @ \ I ȍH v 𐏏 ɂ Ă ܂ BNext, we prove (b) Suppose that g f is surjective Let z 2C Then since g f is surjective, there exists x 2A such that (g f)(x) = g(f(x)) = z Therefore if we let y = f(x) 2B, then g(y) = z Thus g is surjective Problem 338 In each part of the exercise, give examples of sets A;B;C and functions f A !B

6 If G Is A Group Define The Subsetz G G G Chegg Com

Web Northeastern Edu

A W F b N G b Z X ɂ́A ܂ ܂ȍ I G l M ܂܂ Ă ܂ B ̈ӎ ڊo ߂ A o C u V V t g A n g J A The Problem Let $X, Y, Z$ be sets and $f X \to Y, gY \to Z$ be functions (a) Show that if $g \circ f$ is injective, then so is $f$ (b) If $g \circ f$ isLet f ∶X →Y and g ∶Y →Z be injections, and let a;b ∈X Suppose that g f(a) =g f(b) Since g is injective, we must have f(a) =f(b) Since f is injective we must have a =b Therefore g f is injective Problem 95 Let f and g be bijections Then f and g are both injections, so by problem 94 we know g f

What Is The Solution To F X G X Select Each Correct Answer A 3 B 1 C 0 D 1 E 2 Brainly Com

Find The Derivative Of The Given Function At The Chegg Com

Title datasheetpcetm80 Author Pia Created Date AMA,b, and define G(x) = Z x a f(t)dt where a ≤ x ≤ b Then G0(x) = d dx "Z x a f(t)dt # = f(x) G(x) = Z x 0 sin2(t)dt G0(x) = sin2(x) H(x) = Z x3 0 sin2(t)dt H0(x) = 3x2 sin2(x3) 1 Integration by Substitution Let u = g(x) and F(x) be the antiderivative of f(x) Then du = g0(x)dx and Z f g(x) g0(x)dx = Z f(u)du = F(u)C Also, Z b a f gF B J A } Z s Ƃ́A w I Ȍ n A } Z s 𑨂 H 邱 ƁB A } T C G X A J f ~ ́A Ì Ŗ𗧂 H I ȃA } Z s Nj Ă ܂ B Ⴆ A ɂ ẮA f B J A } Z s ̌ n A O I Ȉ S ̌ s A \ m ɋL ڂ A b g i o ɂ 萻 i Ǘ Ă ̈ȊO ̎g p F ߂܂ B

Copula Based Frequency And Coincidence Risk Analysis Of Floods In Tropical Seasonal Rivers Journal Of Hydrologic Engineering Vol 26 No 5

5 Complex Chebfuns Chebfun

Ĉ l l S Ⴄ g ̂Ƃ ו ܂Ŋώ@ Ȃ A X ̃I W i j \ Ɏd グ 邽 ߁A m Ȍ ʂɂ Ȃ ܂ B J } ł́A G X e e B b N ̃ b g 肾 ɁA { f B A t F C X g g g ܂ŁA ʂɔ l X ȏ ̃f b g ̕ 邽 ߂̃T r X p ӂ Ă ܂ I

Alphabet A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O

Pdf Attack Defense Trees Semantic Scholar

Using Numcases Environment In Align Environment Tex Latex Stack Exchange

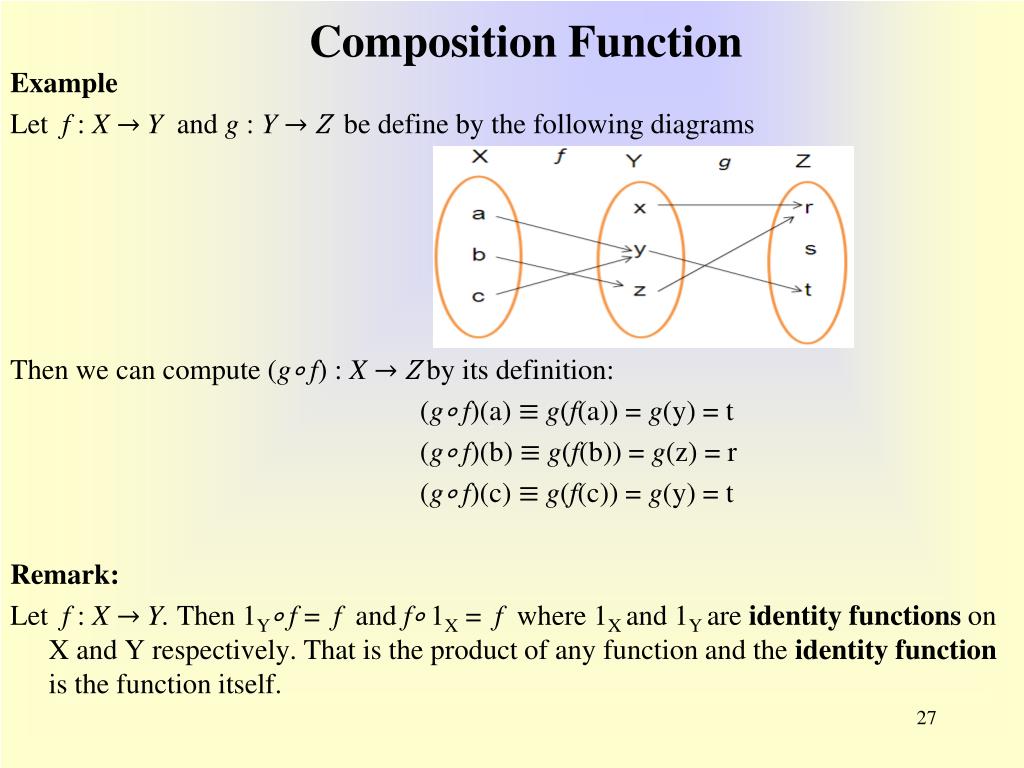

Function Composition Wikipedia

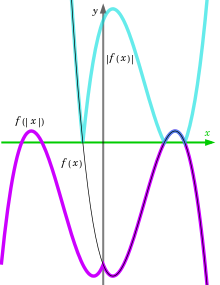

Let F X X And G X 0 X In Z X 2 X In R Z Then A Lim X 1 F X Exists B F X Is Not Continuous At X 1 C Lim X 1 G X Exists D G X Is Continuous At X

G Is For Googol A Math Alphabet Book David M Schwartz Amazon Com Books

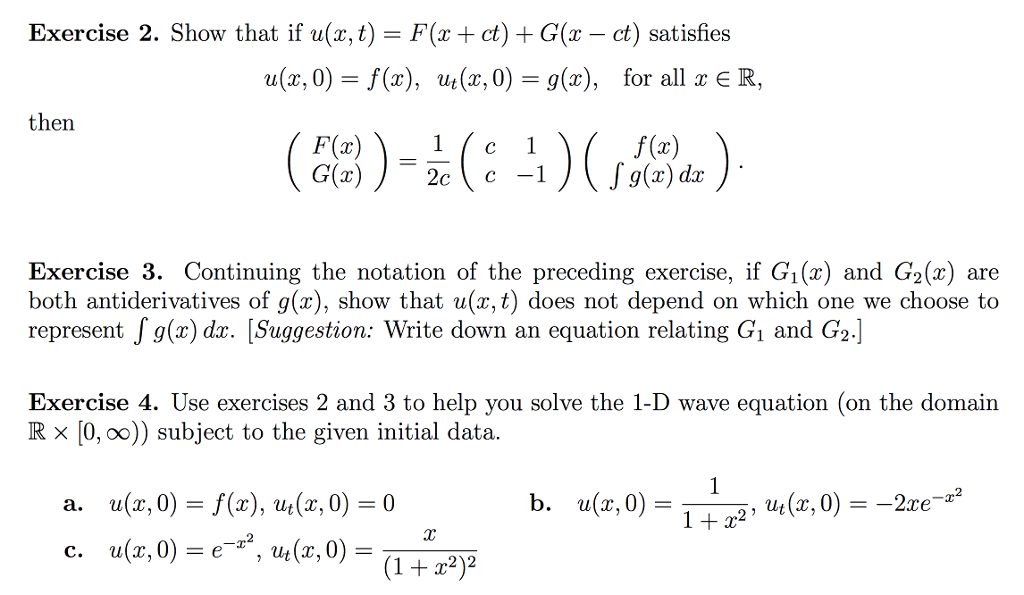

Solved Exercise 2 Show That If U X T F Ct G X Ct Chegg Com

Function Mathematics Wikipedia

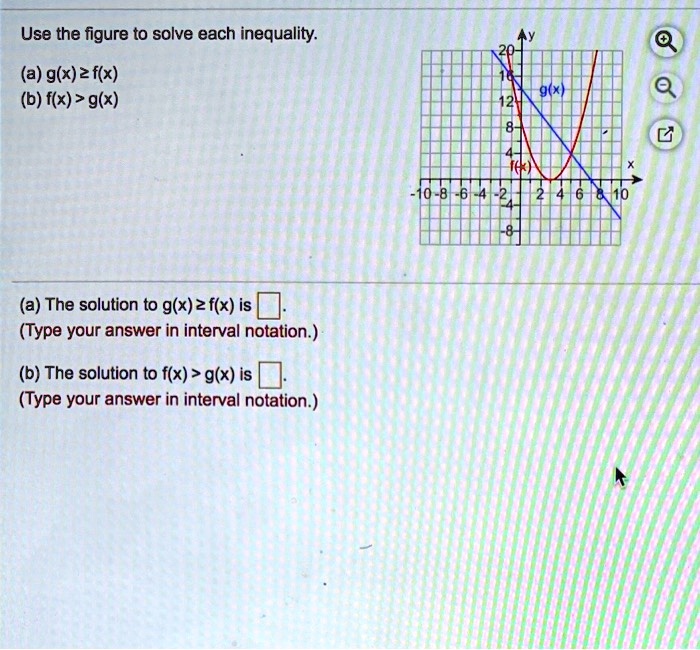

Solved Use The Figure T0 Solve Each Inequality A G X Z Flx B F X G X A The Solution To G X Z F X Is Type Your Answer In Interval Notation B The Solution To

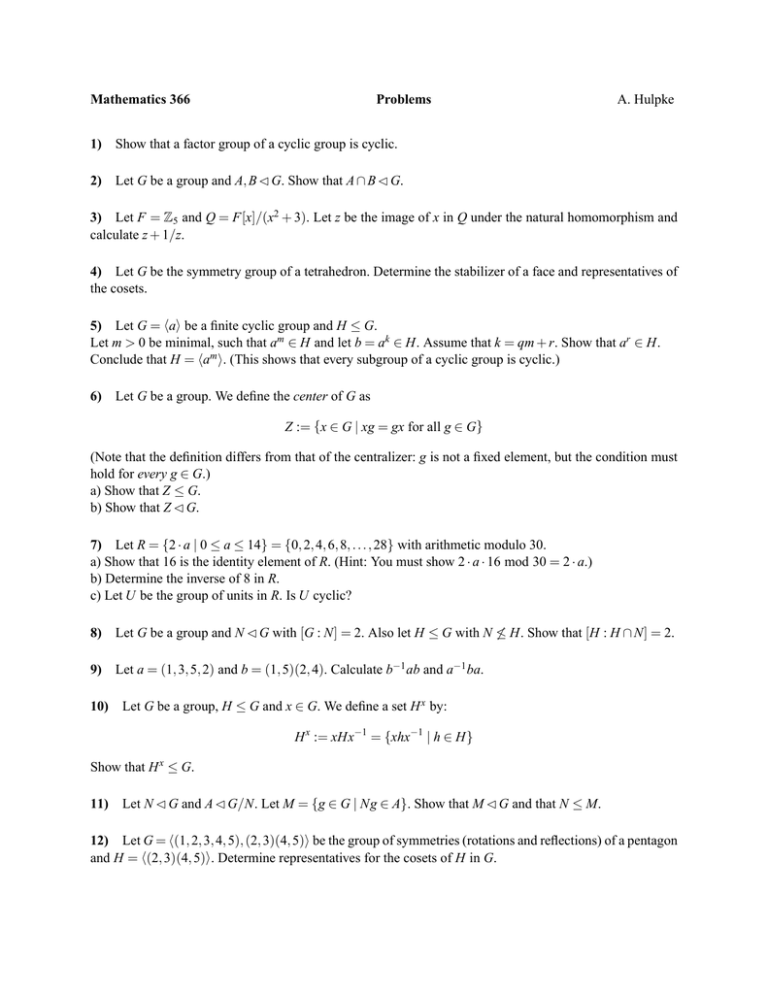

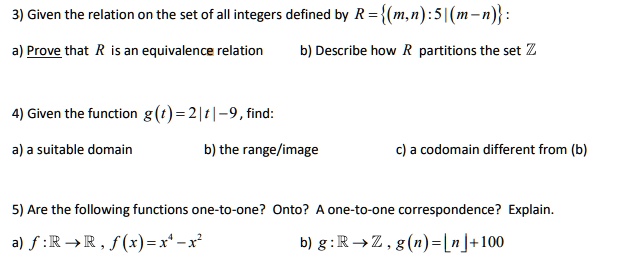

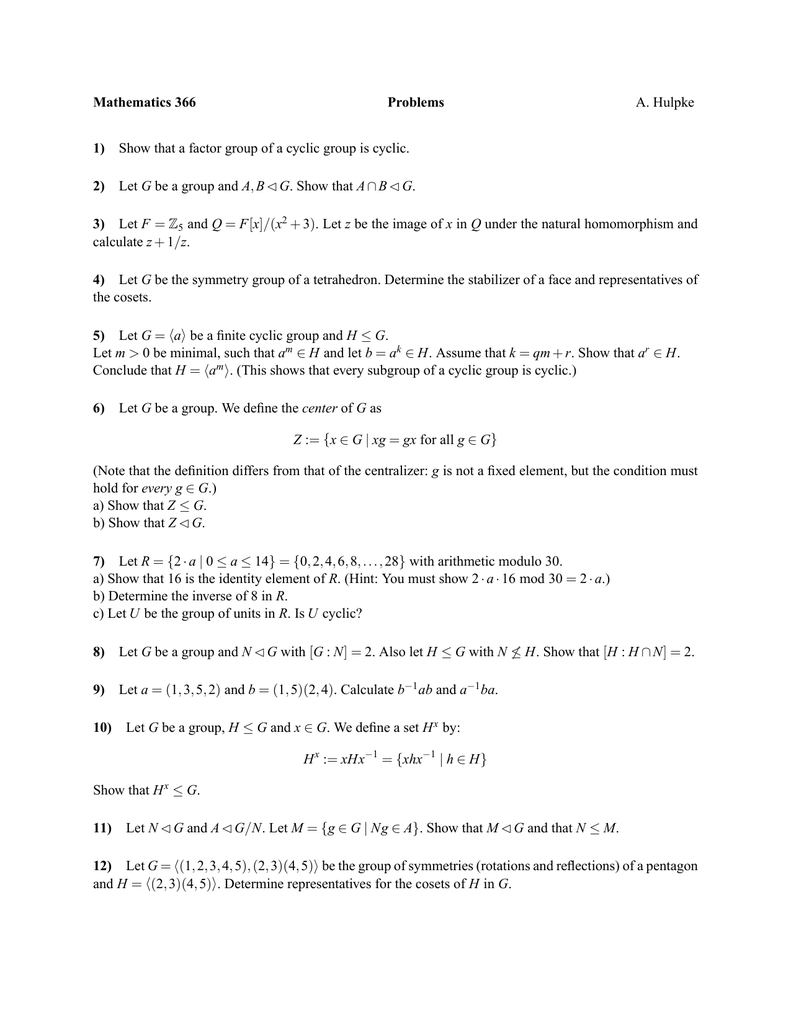

Mathematics 366 Problems 1 2

Predicate Logic Or Fol Chapter 8 Propositional Logic

Autoencoders Guy Golan Lecture 9 A Ppt Download

Please Help Functions F X And G X Are Defined Below Tex F X Sqrt X 2 Brainly Com

Let F B A And G A B Be Functions A Prove Homeworklib

Nesinkoyleri Org

Lol What Is Your Family S Latin Credo Click Here Http Fb Gg Play Funquizgame En Facebook

Page 8 W Zz High Resolution Stock Photography And Images Alamy

Arxiv Org

Solved 3 Given The Relation On The Set Of All Integers Defined By R M N 5 M N A Prove That R Is An Equivalence Relation B Describe How R Partitions The Set Z

Describe The Transformation Of F X To G X G X O A F X Is Shifted Down 2 Units To G X O B Brainly Com

Partial Derivative

Math Mit Edu

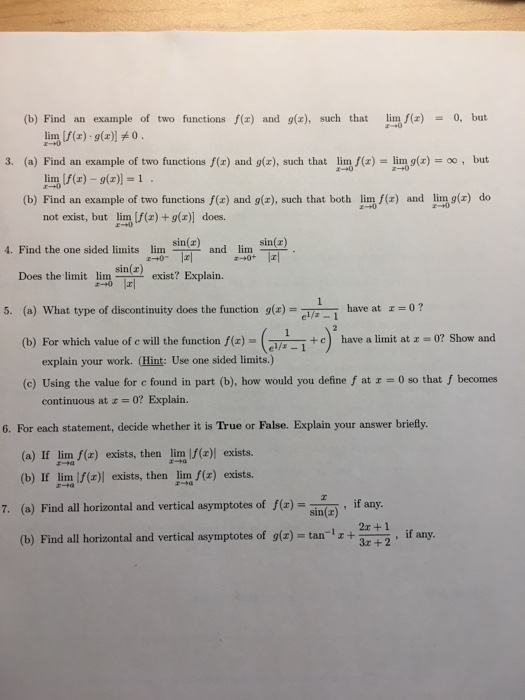

B Find An Example Of Two Functions F X And G Z Chegg Com

Mathematics 366 Problems 1 2

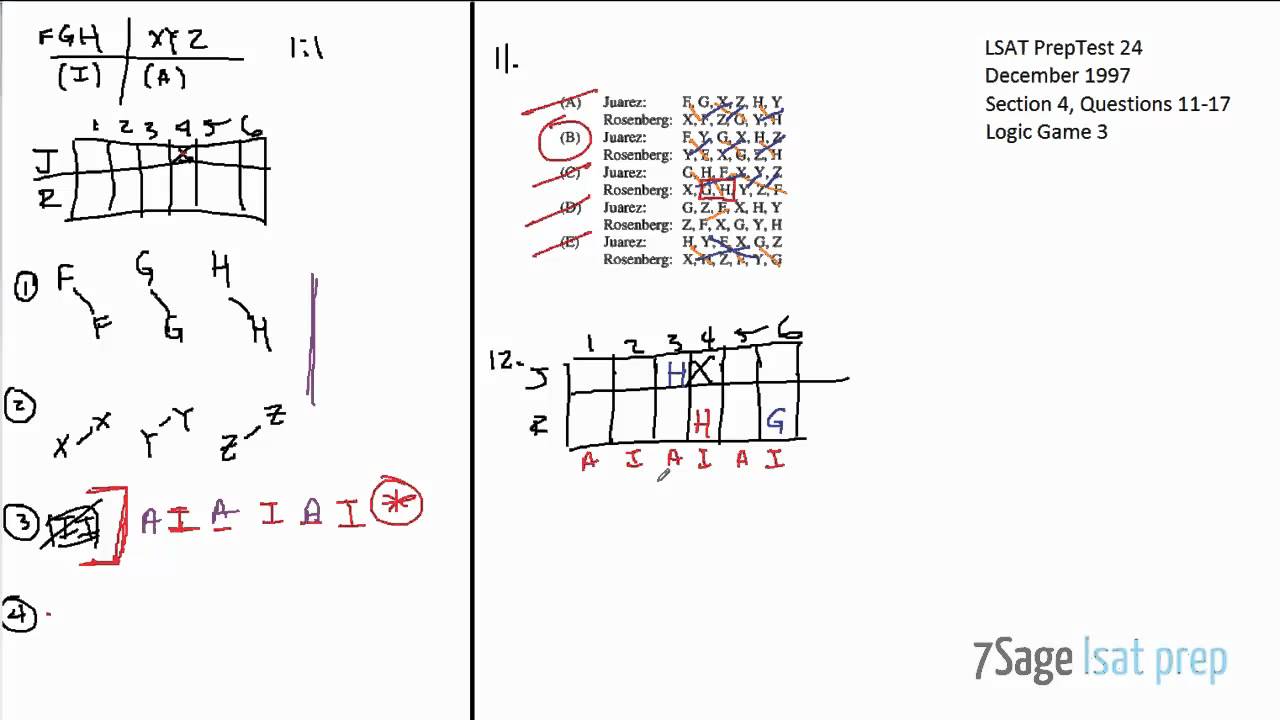

Lsat Preptest 24 Logic Game 3 Full Tutorial Questions 11 17 Youtube

A15dr H Ccc4lm

Colorful A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y X Z Text In Paper Cut Style Stock Illustration Download Image Now Istock

Amazon Com Initials Wedding Cake Topper Letter Cake Topper Wedding Cake Topper A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Grocery Gourmet Food

Math Upenn Edu

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Cartoon Text Font Hand Drawing Vector Letters Stock Illustration Download Image Now Istock

Draw The Diagram Of The Following Expressions Using Only Nand Gates Assume All Inputs Are Available Both Uncomplemented And Complemented Do Not Simplify Equations A F Ab D B D D B G Z X Study Com

Solved Find Dz Dx And Dz Dy A Z F X G Y Dz Dx 0 0 F X Chegg Com

Determine Where F X G X From The Graph A X 2 X 2b X 2 X 0 X 2c X 0 X Brainly Com

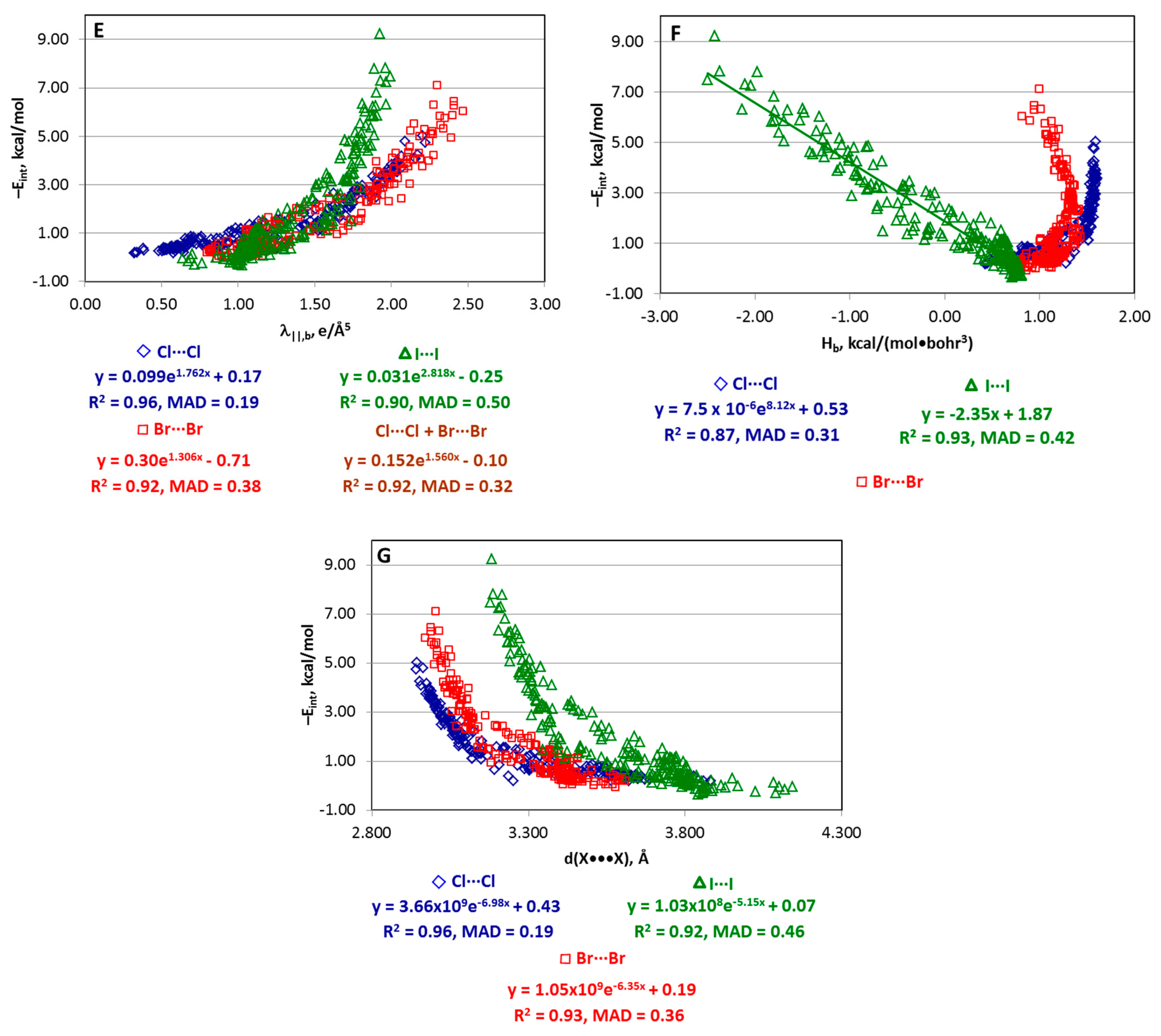

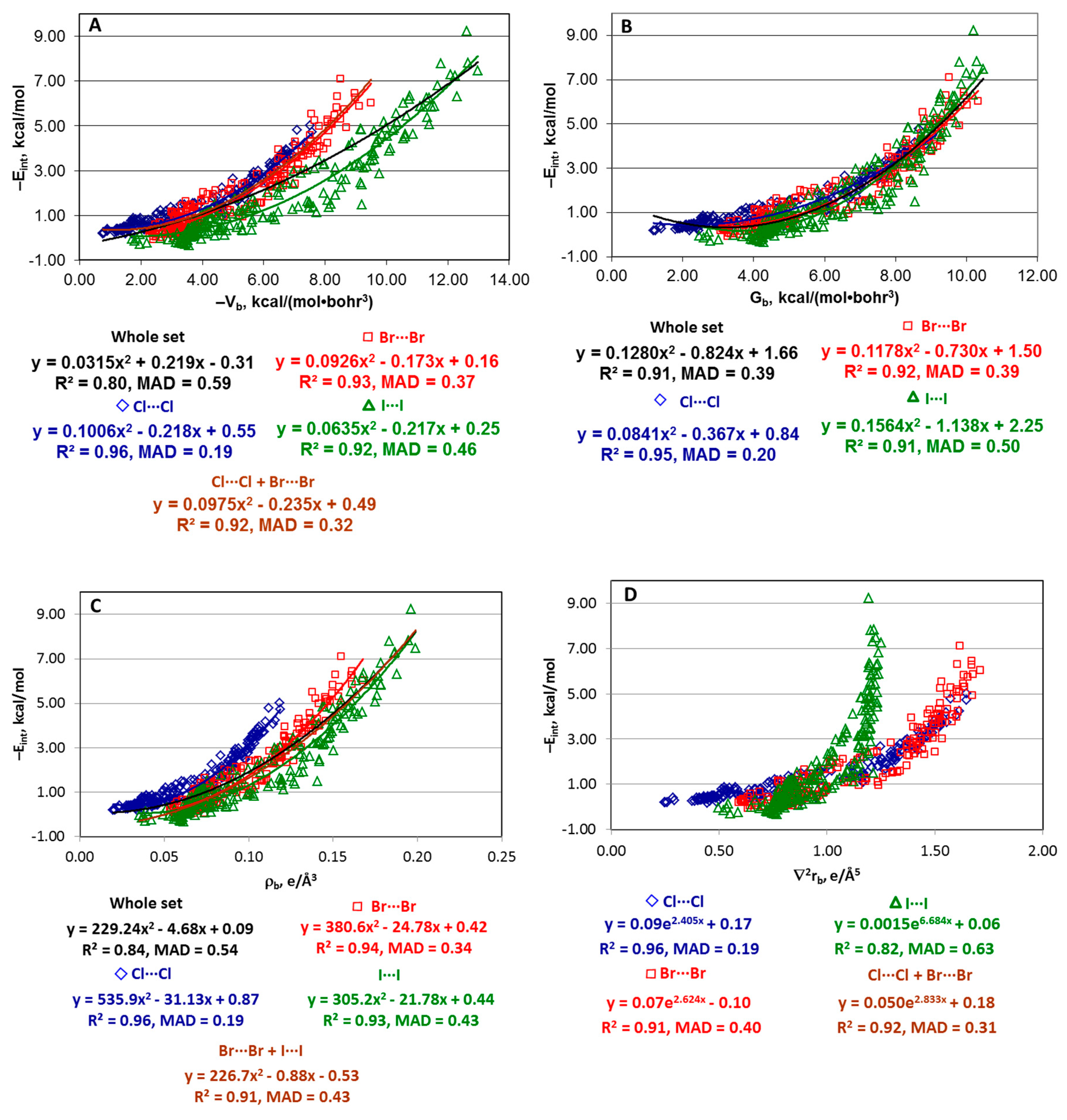

Molecules Free Full Text Relationships Between Interaction Energy And Electron Density Properties For Homo Halogen Bonds Of The A Ny X X Z B M Type X Cl Br I Html

Icu Hsuzuki Github Io

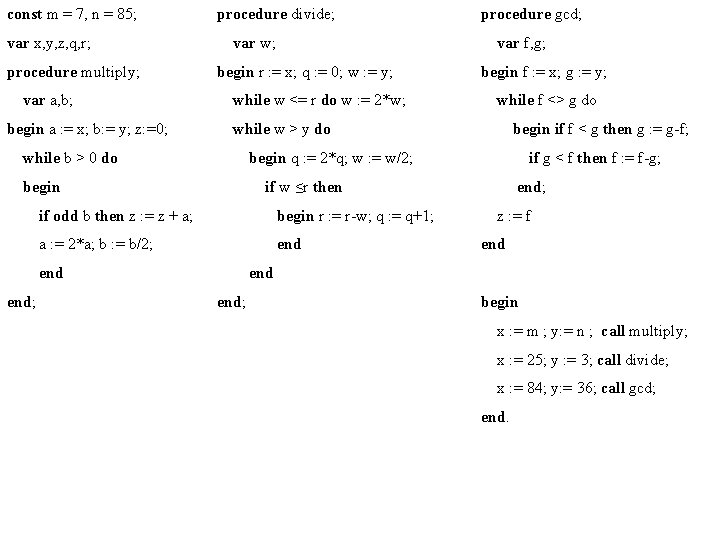

Pl 0 Parser Const M 7 N 85

Europeanreview Org

Swimming Energy Of Muskrats And Sea Otters By Mark Charnogorsky

The Triple Integral Remark The Triple Integral Of F Over The Region X Y Z X Ye A B A X Y B X G X Y Z H X Y

Math Ucsd Edu

11 Discrete Structures Discrete Structures Unit 5 Ssk3003 Dr Ali Mamat Ppt Download

Math Gmu Edu

Solutions For Problem Set 4 A Consider The Polynomial Ring R Z X

Elsa Berkeley Edu

1 A 6 Points Let F A B And G B C Be Two Homeworklib

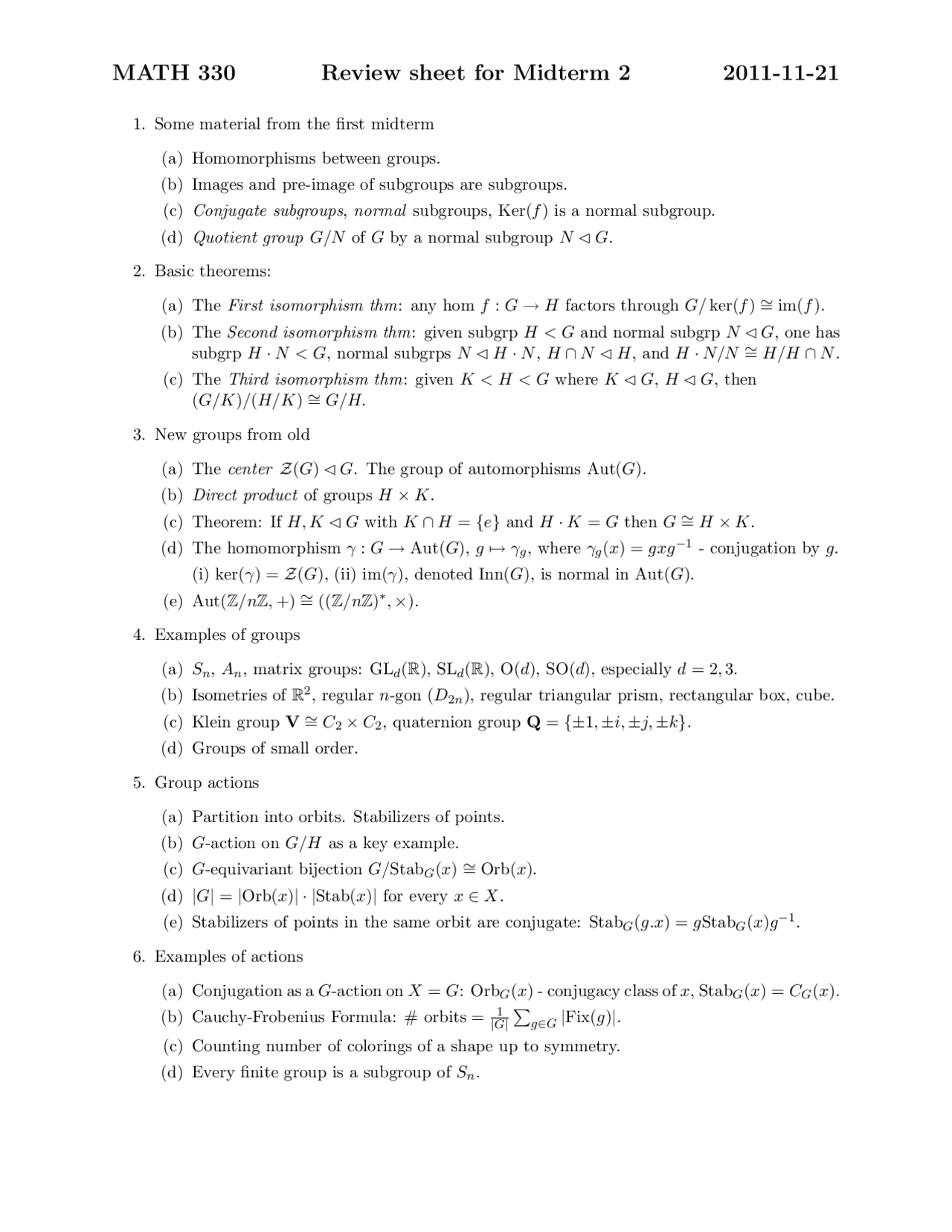

Review Sheet For Midterm Exam 2 Abstract Algebra I Math 330 Docsity

Molecules Free Full Text Relationships Between Interaction Energy And Electron Density Properties For Homo Halogen Bonds Of The A Ny X X Z B M Type X Cl Br I Html

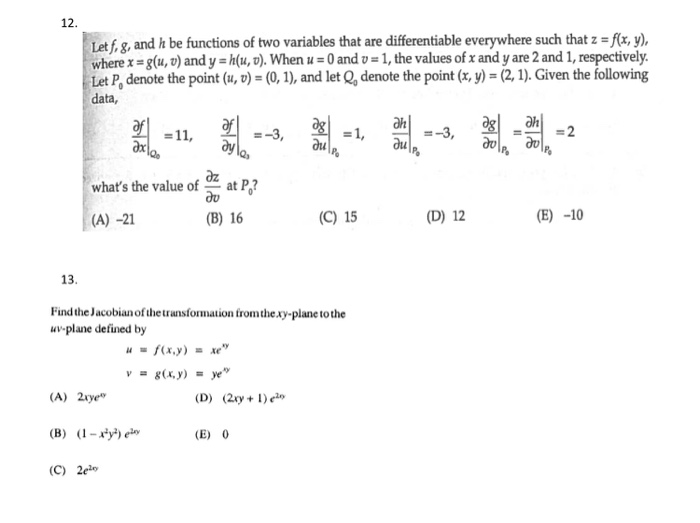

Solved Let F G And H Be Functions Of Two Variables That Chegg Com

Unit Vi

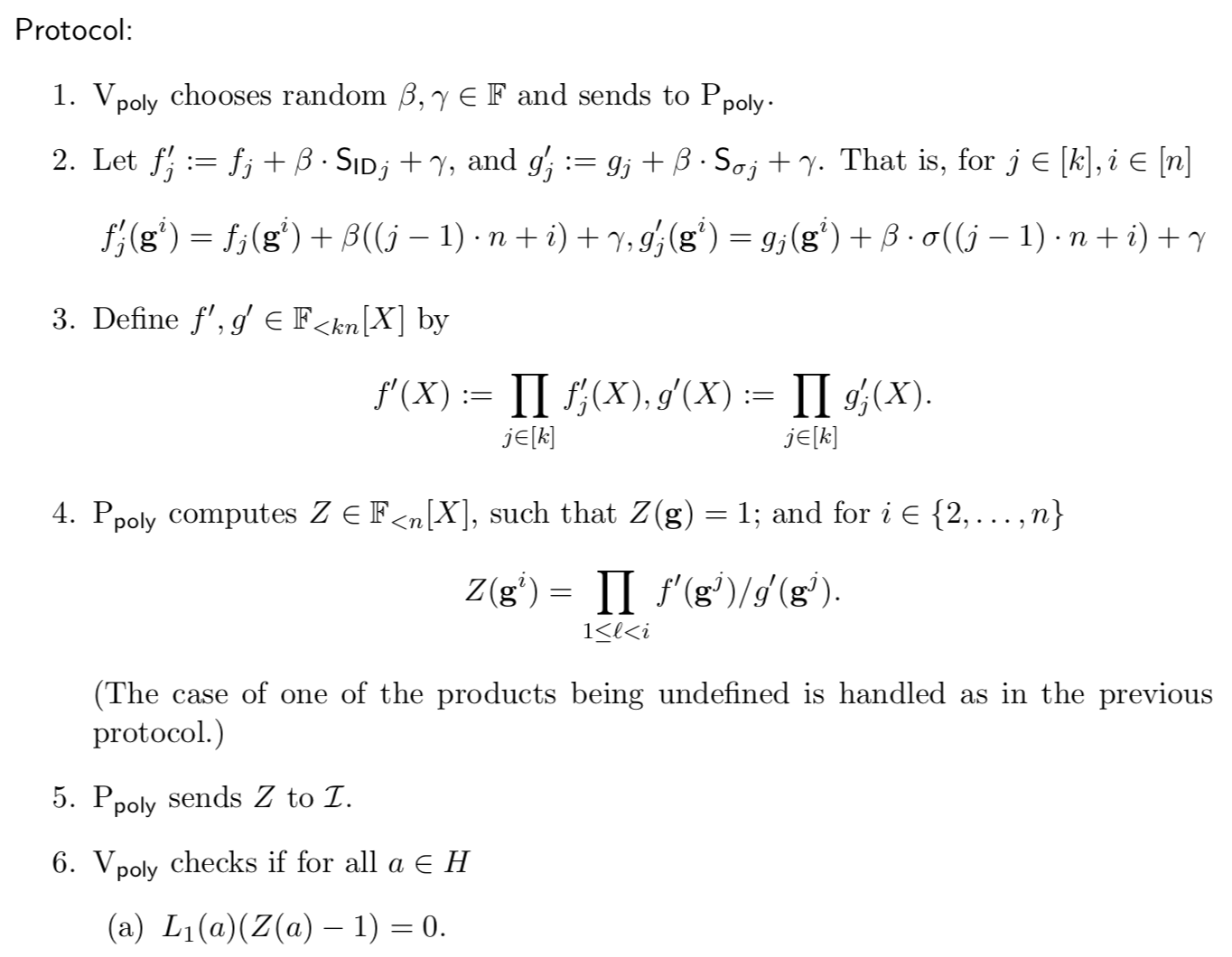

Zkp Plonk Algorithm Introduction By Star Li Medium

An Example Presents Multi Sentence Requirement Req And The Download Scientific Diagram

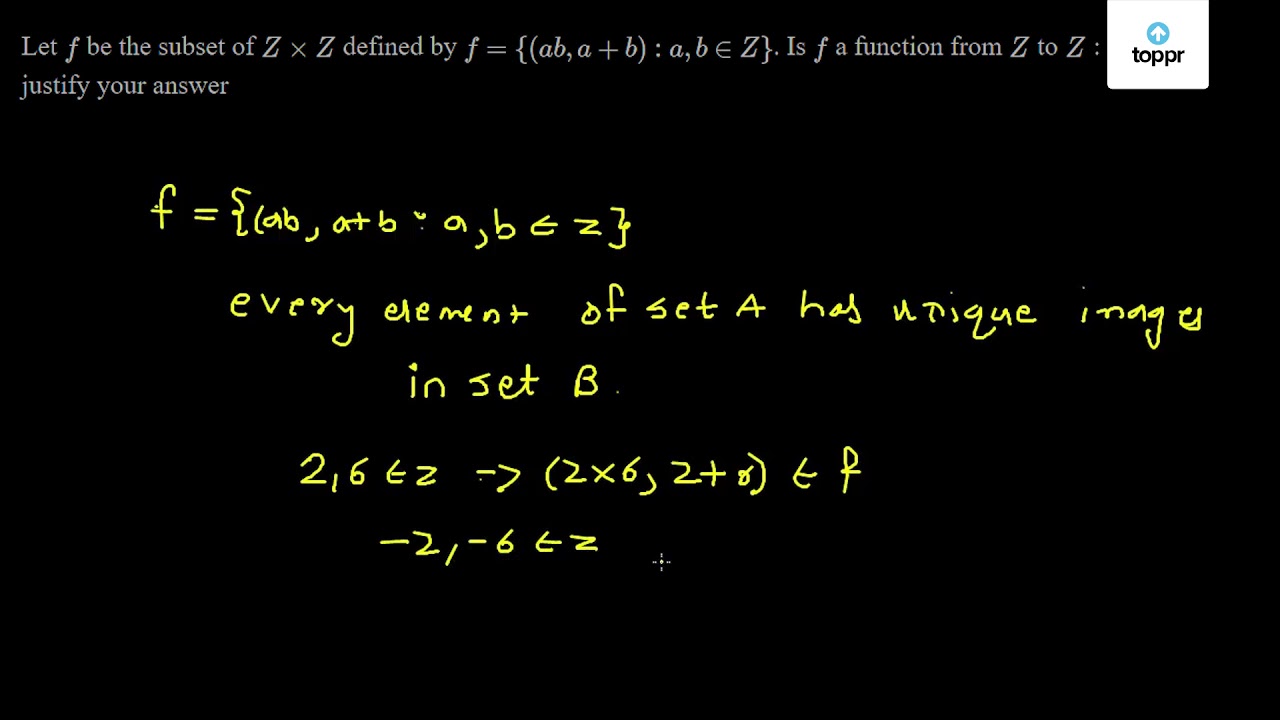

Solved Let F Be The Subset Of Z Z Defined By F Ab A B A B Z Is F A Function From Z To Z Justify Your Answer

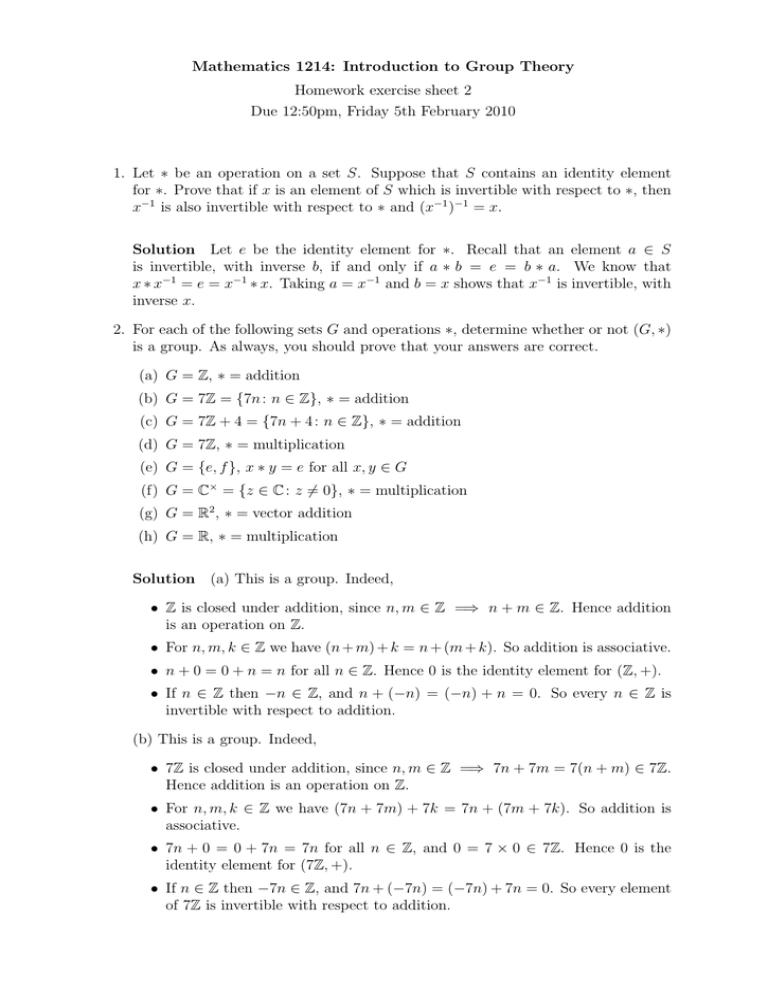

Mathematics 1214 Introduction To Group Theory Homework Exercise Sheet 2

Ppt Title Functions Limits And Continuity Powerpoint Presentation Free Download Id

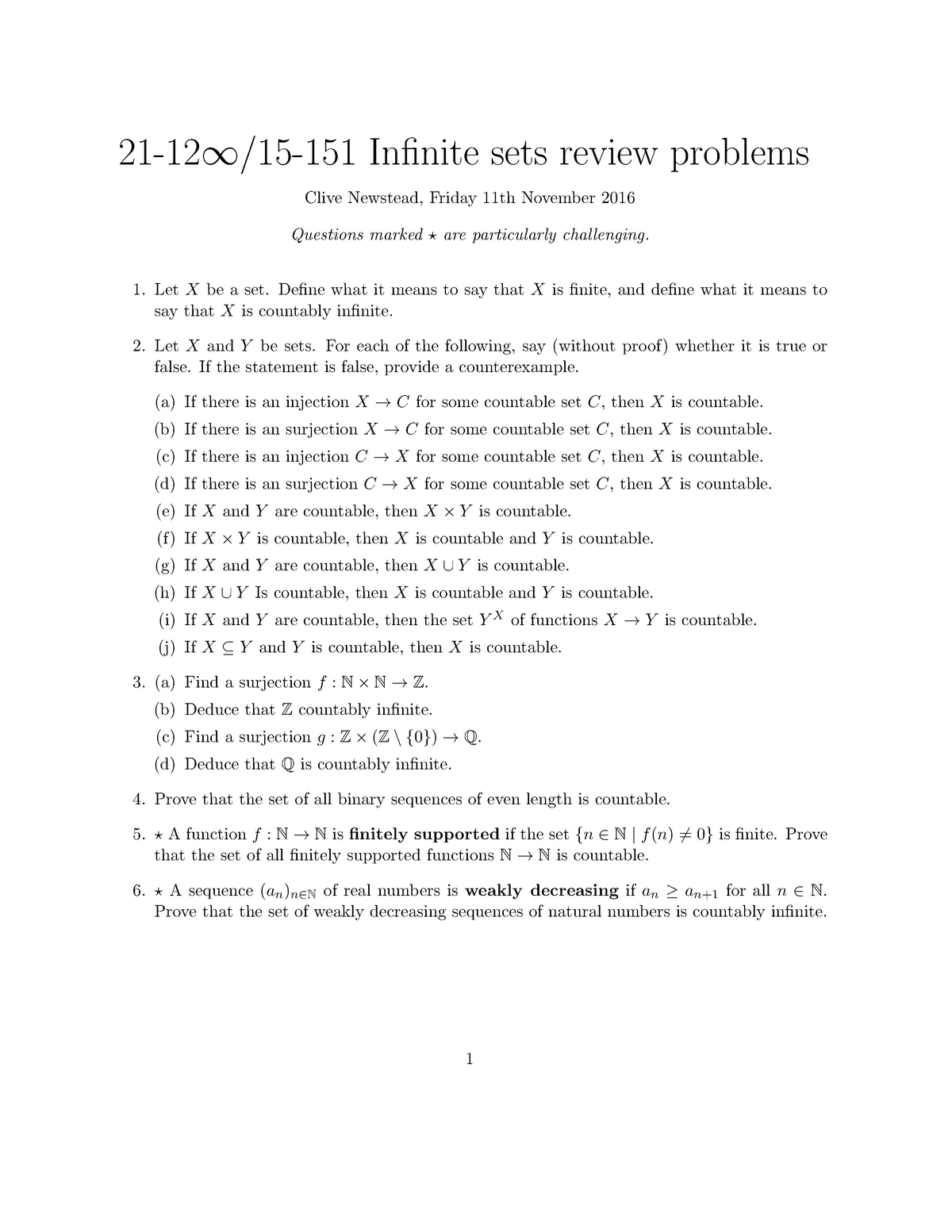

Infinite Sets Review Questions 21 128 Mathematical Concepts And Studocu

Faculty Math Illinois Edu

Degruyter Com

Function Composition Wikipedia

F X Y F X F Y

The Universal Coefficient Theorem Renzo S Math 571

Stat Berkeley Edu

Services Math Duke Edu

Math Mcgill Ca

10 October 06 Foundations Of Logic And Constraint Programming 1 Unification An Overview Need For Unification Ranked Alfabeths And Terms Substitutions Ppt Download

F X X2 What Is G X F X G X 2 2 15 Brainly Com

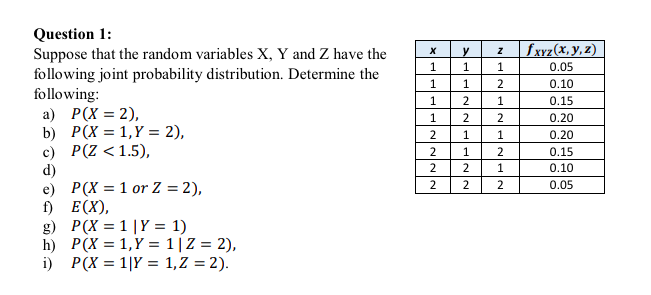

Answered Question 1 Suppose That The Random Bartleby

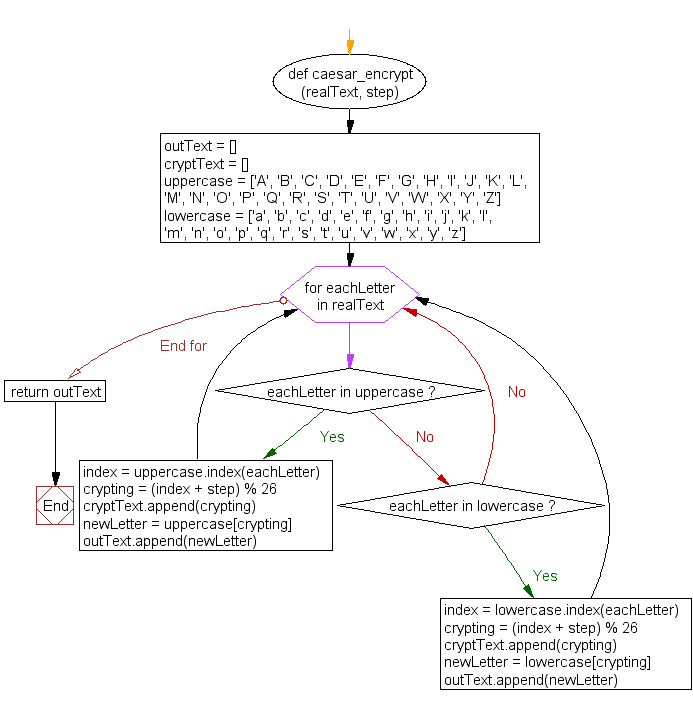

Python Create A Caesar Encryption W3resource

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Cartoon Text Font Hand Drawing Vector Letters Stock Illustration Download Image Now Istock

Cse Unl Edu

Y F X

Maths Dur Ac Uk

2 A Prove The Product Rule For Complex Functions More Specifically If F Z And G Z F Z G Z Is Also Analytic And Homeworklib

F G H Are Continuous In 0 A F A X F X G A X G X 3h X 4h A X 5 Then Prove That Int 0 Af X G X H X Dx 0

F X X 2 What Is G X G X A G X 4x B G X 4x 2 C G X 16x 2 D G X 1 4x 2 Brainly Com

Solved Find 02 0x And Dz Dy A Z F X G Y Drox Ozlay Oo Chegg Com

Math Brown Edu

What Is The Jacobian In This Context Mathematics Stack Exchange

Solved Find Dz Dx And Dz Dy A Z F X G Y Dz Dx 0 0 F X Chegg Com

Let F X And G X Be Bijective Functions Where F A B C D To 1 2 3 4 And G 3 4 5 6 To W X Y Z Respectively Then Find The Number Of Elements In The Range Set Of G F X

Dornsife Usc Edu

コメント

コメントを投稿